If you have ever tried to decide what an aging parent needs next, you already know how quickly a practical question can turn into a family argument. One sibling focuses on safety, another worries about money, and a third feels shut out. Meanwhile, your parent may feel talked about instead of listened to.

Families often get relief when they set up clear authority and a shared care plan early, before the first emergency. Jarvis Law Office works with families on elder law planning, memory care planning, and decision-making documents, and the firm also runs community workshops that cover estate planning and long-term care topics. A Jarvis Law Office attorney put it this way: “Most fights start because no one knows who has authority, and no one feels heard. Clear documents and a care plan can keep the focus on the older adult.”

To ground this in reality, it helps to look at the numbers. A roundup of aging data shows that life expectancy has been rising again after the pandemic-era dip, and that chronic conditions are common in later life. You can review the full set of figures here: SeniorLiving’s statistics about seniors.

This article explains why elder care disputes start, what documents and habits lower conflict, and what courts typically look for if a family still ends up in a legal fight.

Why elder care disagreements can escalate faster than people expect

People sometimes assume sibling conflict is the real problem. Often it is the stress of aging, plus unclear authority, plus a timeline that feels too tight. Longer life spans mean more years where health can shift, and more years where a family has to make decisions together.

According to data, the average U.S. life expectancy in 2021 was 76.4 years, and it rose to 77.5 years in 2022. The same summary reports a gap by sex in 2022, with women at 80.2 years and men at 74.8 years. Those averages hide a lot of variation by income, geography, and health history, but they point to a simple reality, many families will be making care decisions for a longer stretch of time than they expected.

Loneliness and isolation also add pressure. Our statistics page notes that about a quarter of seniors can be affected in ways that hurt both mental and physical health. If your parent lives alone, or has lost friends, or no longer drives, the risk of missed medications, falls, and scams rises, and families start reacting instead of planning.

Then there is the health side. That same data summary reports that almost 95 percent of adults 60 and older have at least one chronic condition, and nearly 80 percent have two or more. It also lists conditions that show up often in later life, including arthritis, diabetes, and obesity. Chronic illness does not automatically mean loss of independence, but it does mean the family needs a system for decisions, updates, and support.

All of that creates the setting where small triggers cause big reactions, which is why the next step is to get clear on one question families often skip, who can legally act for your parent.

Authority basics: who can act for an older adult

Closeness is not legal authority. Being the adult child who lives nearby does not automatically grant the right to manage bank accounts or make medical choices. A clear plan usually includes a few core documents and some practical steps that support them.

Financial authority and the power of attorney

A financial power of attorney allows an older adult, while they still have the capacity to choose, to name an agent who can handle tasks such as paying bills, dealing with insurance paperwork, and managing accounts. Without it, banks and other institutions often refuse to discuss details with anyone but the account holder.

Conflict shows up in predictable ways:

- One sibling starts “helping” with bills and expects reimbursement with no written agreement

- Multiple people call the bank and get different answers

- A parent’s checks bounce, and siblings blame each other instead of fixing the system

A good plan also includes guardrails, such as recordkeeping expectations, limits on gifts, or a second set of eyes on major transactions.

Health care authority and medical choices

Health care decision documents matter because hospitals and clinics want clarity. If your parent cannot communicate, clinicians look for the person authorized to consent, access records, and coordinate care. Without that structure, family members can argue at the bedside while staff wait.

Even when siblings agree on the big picture, the details can divide them. One person may push for hospital-based care, another may favor home support, and your parent’s preference might not match either view. Written directions and a designated decision-maker reduce guesswork at the moment decisions feel most urgent.

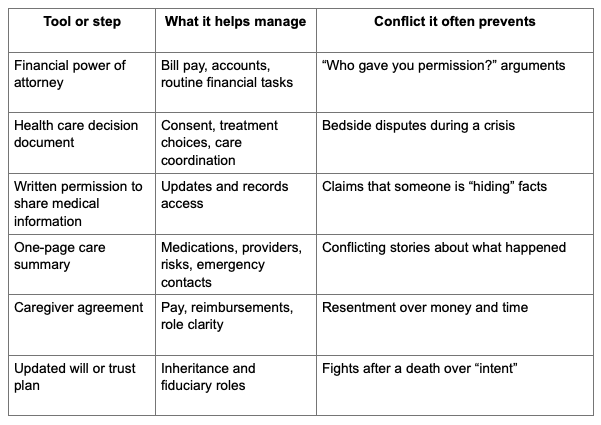

A simple table that keeps roles and tools straight

If your family is feeling overwhelmed, use the table below as a starting point for a calmer conversation. It summarizes common tools and the disputes they often prevent.

Once a family understands authority, the next friction point is safety, especially if memory changes enter the picture.

Memory changes and safety decisions: why timing matters

Memory change is not only about diagnosis. It is about risk, and risk shows up in daily life. A parent can sound sharp in conversation and still miss medications, forget bills, or fall for a phone scam.

Our statistics data summary also highlights that leading causes of death include heart disease and cancer. Those conditions can involve medication changes, fatigue, and hospital stays, which add complexity to care even without memory decline. If memory issues are present too, the family needs a plan that can adjust quickly.

Early warning signs families disagree about

Siblings often argue because they see different pieces of the picture. One sibling sees missed appointments. Another sees a parent who can still tell stories clearly. Both can be true.

Signs that deserve calm attention include:

- Repeated missed doses or double dosing

- Confusion about bills or new “subscriptions”

- Getting lost on familiar routes

- Falls or unexplained bruises

- Changes in hygiene or household safety, such as leaving the stove on

The goal is not to diagnose at the kitchen table. The goal is to respond to risk with respect for autonomy.

What memory care planning looks like in real life

For many families, “memory care planning” is a series of steps rather than one big leap:

- A medical evaluation and documented baseline

- A plan for medication management

- Home safety changes, such as better lighting and fall prevention

- A driving plan, including how decisions will be made and who will talk with your parent

- A plan for supervision that can grow over time

A system like this reduces panic, and it also helps families document decisions in a way that makes sense to clinicians and, if needed, to a court later. Once safety planning starts, many families then notice another risk that can inflame sibling conflict fast, undue influence.

Protecting an older adult from undue influence and financial abuse

Financial abuse is not always obvious. It can start as “help” and slowly become control. Isolation, grief, and dependence can make older adults easier to pressure, and family members may disagree about whether a new friend, neighbor, or romantic partner is supportive or suspicious.

The aforementioned statistics page notes projections that the U.S. centenarian population could grow sharply over the next 30 years, with estimates of about 422,000 Americans age 100 and older in 2054, and global projections nearing 4 million. That growth matters because longer lives can mean more years where a person’s vulnerability changes, especially if they live alone or have health issues.

Red flags worth taking seriously

You do not need to accuse anyone. You do need to pay attention to patterns, such as:

- Sudden changes to a will or beneficiary forms with no clear explanation

- A new person screening calls or blocking visits

- Unusual bank withdrawals or checks written to cash

- A parent expressing fear about “upsetting” a helper

- A caregiver moving in and isolating the parent

If you suspect problems, focus on facts and documentation. Neutral professionals, such as care managers, can sometimes help document needs without turning the situation into a sibling showdown.

Practical safeguards that lower risk

Safeguards often look like good management:

- Reduce unnecessary accounts and keep finances organized

- Set up automatic bill pay where appropriate

- Use account alerts for large transactions

- Require routine record sharing for anyone acting as an agent

- Choose fiduciaries who can tolerate transparency

This approach also protects honest caregivers, because good records reduce suspicion. That leads directly into the most common sibling tension point, the caregiver child.

The caregiver child problem: money conversations families avoid

In many families, one adult child becomes the default caregiver. Sometimes it is geography. Sometimes it is personality. Sometimes the parent refuses outside help. Over time, the caregiver can feel isolated and financially strained, while other siblings feel excluded or suspicious.

A fair plan starts by naming reality. Caregiving takes time. It also costs money, even if the caregiver never asks for payment. Gas, missed work, and out-of-pocket supplies add up. If no one talks about money until a crisis, conflict often follows.

Here is a simple way to start the conversation without turning it into a scorecard:

- What tasks need to happen each week?

- Who owns each task?

- What expenses are recurring, and who pays them?

- How will reimbursements work, and what proof is needed?

- How will updates be shared so no one feels shut out?

Even a short written agreement can reduce resentment because it replaces assumptions with shared expectations. Once families get clearer on roles, the next fear tends to surface, “How long can we afford this level of care?”

Long-term care costs and Medicaid planning: separating myths from reality

Long-term care can become expensive quickly once support shifts from occasional help to daily supervision or around-the-clock care. Many families also misunderstand what Medicare pays for, which can trigger rushed decisions.

Medicaid planning is a broad term people use to describe lawful steps that help families prepare for possible long-term care needs. The details vary by state, so families should get qualified guidance rather than relying on hearsay. Still, the shape of the conversation is similar for many households.

Common myths that drive sibling conflict include:

- “The nursing home will automatically take the house”

- “We can transfer everything to one child and be fine”

- “We should wait until the last minute”

A calmer approach separates the questions:

- What level of care is needed now?

- What level of care is likely in one year, three years, five years?

- What assets exist, and who knows the full picture?

- What help can family provide, and what help must be paid for?

Answering those questions requires facts, and facts are easier to share when the family has a system for communication and documentation.

Communication habits that reduce suspicion and keep everyone aligned

Many elder care disputes are not really about the parent’s needs. They are about trust. Siblings suspect each other because information is inconsistent, or because one person controls updates and others feel frozen out.

A system does not need to be fancy. It needs to be consistent.

A practical family meeting agenda

A family meeting can be a phone call, a video call, or coffee at the same table. Use a simple agenda:

- Current health status and upcoming appointments

- Medication list and recent changes

- Current living situation and safety concerns

- Monthly expenses and who is paying what

- Tasks and who owns each one through the next month

- Next meeting date and how updates will be shared

If your parent can participate, keep the tone respectful and direct. Ask what matters to them, not only what worries you.

A documentation system that fits real life

Families do better with a shared system that is easy to use:

- A shared folder with scans of key documents

- A shared calendar for appointments

- A monthly expense summary

- A one-page care summary for urgent calls

Documentation reduces “he said, she said,” which is often what turns a disagreement into a legal threat. Still, some families reach a breaking point, and it helps to know what happens then.

If conflict escalates: what courts tend to look at, and how families can prepare

Guardianship cases and related actions are serious. Courts often treat them as a last resort because they can remove rights from an older adult. Family conflict alone should not be the reason a case goes forward. Judges typically want evidence about capacity, risk, and whether less restrictive options exist.

Documentation often matters, such as:

- Medical records describing cognition and decision-making ability

- Records of unpaid bills, unsafe conditions, or repeated harm

- Bank statements showing unusual transactions

- Notes from neutral professionals, such as care managers

- Evidence that the family tried to use existing authority documents before asking a court to step in

A pattern that often backfires is making public accusations without evidence. Another is blocking family contact with no safety reason. If you are worried about undue influence or misuse of funds, focus on protecting your parent with facts and appropriate help.

Understanding what courts look for can also guide your family back to prevention, because most families would rather fix the system than fight in court.

A practical checklist you can use this week

If you want a starting point that feels manageable, use this checklist and keep it simple:

- Identify who currently has legal authority for finances and for health care

- Confirm where documents are stored and who can access them in an emergency

- Create a one-page care summary for medical visits and urgent calls

- Set a monthly update routine and keep it consistent

- Track expenses with receipts and plain summaries

- Plan for the next likely step, such as home help, assisted living, or memory care

Life expectancy has risen again, chronic illness is common in later life, and many families will be managing care for years, not months. A clear authority plan and a steady communication system can keep those years safer and calmer.

The next time a hard decision comes up, you want your family talking about the choice itself, not arguing about who has the right to speak.